Hurricanes, Lemonade, and the Velocity of AI Spending

Why “Are We in a Bubble?” is the Wrong Question.

Nvidia delivered blowout results last week.

It brought to mind hurricanes.

I remember hearing an analyst on CNBC explain, about a decade ago, that when a storm hits Florida, the local economy doesn’t contract—at least not in the short term. Instead, money sitting quietly inside insurance companies flows back into the world.

Reserves become drywall.

Cash becomes concrete.

Liabilities become labor.

It’s counterintuitive, but hurricanes are stimulative. The local velocity of money rises. Not because something new is created, but because what is broken must be repaired. What was wiped out must be rebuilt. The pace of activity accelerates. Dollars turn over faster than they did the month before. Local families feel none of this “stimulus” in the way we imagine that word. A hurricane doesn’t make a place better. It simply awakens dollars that were sleeping.

On the heels of Nvidia’s report, this phenomenon came to mind as I thought about the “hyperscalers” (Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, and Meta) and the investments they are making in AI infrastructure. Hundreds of billions in cash (parked on balance sheets and sitting comfortably in short-term Treasuries) are now being thrust into the global economy, backed by multi-decade commitments that show no signs of slowing.

But unlike hurricane spending, AI investment isn’t about rebuilding what was lost. It’s about constructing something fundamentally new. Something transformative. In many ways, the hyperscalers are building global power plants, only the output isn’t electricity (though they’ll need plenty of it) but on-demand computing capacity.

Spending today shows up in data centers, fiber networks, cooling systems, energy infrastructure, millions of GPUs, and the teams of people required to build and integrate them—all productive capital. A generative good, not a replacement one. It’s the difference between repairing a roof and building a bridge.

Maybe ten thousand bridges.

When Meta commits $35 billion to data centers, it becomes income to suppliers, wages to workers, revenue to utilities, orders for manufacturers, and long-lived assets that power new applications, seed new businesses, and catalyze new productivity.

The sheer scale of the spending is hard to grasp. It’s so massive that most investors can’t help wondering whether something unsustainable is taking shape—whether the contours of a bubble are forming or already have. And it is, in a very real sense, capital picking up velocity.

I’ve been wondering whether this acceleration, the redeployment of quiet capital into active circulation, might be one of the underappreciated forces beneath the strength of the current economy. Textbooks taught us about the velocity of money. What they didn’t teach was the velocity of capital. Inert savings at today’s scale transforming into productive, fixed assets.

And that makes me think of lemonade.

Those same textbooks often illustrated economic concepts in a two-person economy. Imagine an economy where one person sells lemonade and the other sells cookies. They buy from each other once a week for a dollar. Two dollars change hands. Over a year, GDP is a little over $100. Then they decide to eat and drink twice a week, and GDP doubles to over $200. Not because life improved, but because activity increased.

Velocity matters.

Now scale that dynamic up to the size of the global tech ecosystem. For the past decade, the largest and most profitable companies in the world have generated cash so fast they can’t effectively deploy it.

Corporate treasurers parked the largesse in the safest assets. Quiet returns. Patient dollars.

Then ChatGPT arrived, and the AI revolution began.

Suddenly, that cash had a better home than T-bills.

If a hurricane forces cash to wake up, the AI revolution has pulled it into a race—one with a sprinter’s pace and a marathon’s distance. A race only a handful of firms can run. Again, velocity matters. So does stamina.

Long-term economic growth tends to come from two forces: money moving and productivity rising. The AI investment boom checks both. Skeptics can point to the circular nature of some spending or become unnerved by numbers that are hard to comprehend. But that’s the smaller story. The bigger story—as with the dot-com era—lies in the second- and third-order effects: the efficiencies not yet realized, the applications not yet invented, and the companies not yet created.

For investors, history reveals an important point. The giants of the 1990s (Intel, Cisco, Oracle, Sun Microsystems, AOL, and Yahoo) were early winners of the internet boom, but as the wave matured, leadership changed. New companies emerged, new business models formed, and the next decade belonged to a different set of firms: Google, Amazon, Netflix, Salesforce, Qualcomm, and Apple, to name a few. The winners of the 2000s were not the winners of the 1990s. No matter how big or powerful a company is, most are not adept enough, or led well enough, to make the transition from one wave to the next—Microsoft being the recent exception.

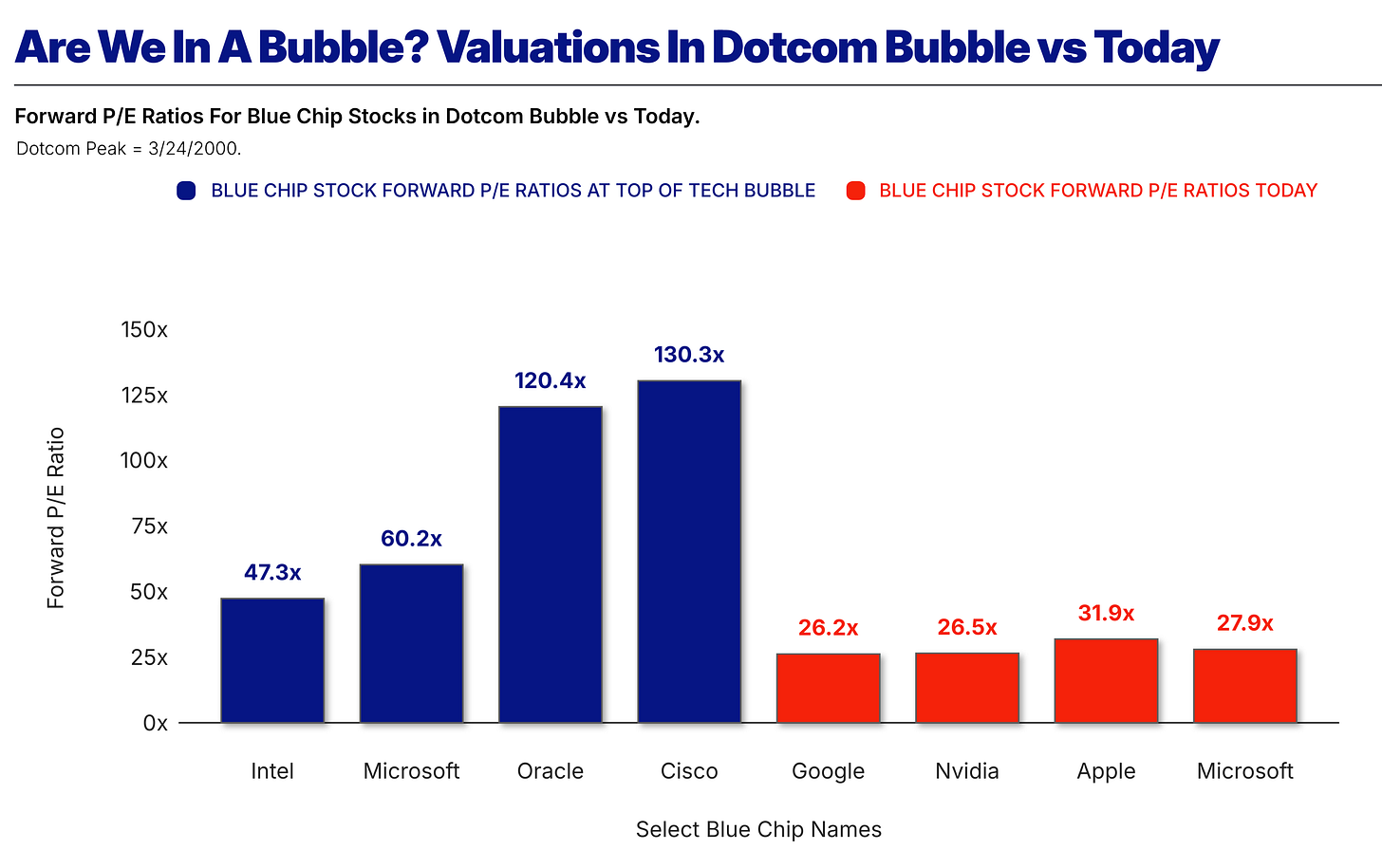

As markets trade near all-time highs, it’s natural to wonder whether we are in a bubble. After all, by early 2000, earnings forecasts proved too optimistic and prices ran too far. Intel traded at almost 50x forward earnings, Microsoft at 60x, Oracle at 120x, and Cisco at 130x. When the earnings didn’t materialize, something had to give.

That something was price, and the bubble burst.

So what about today—are we in a bubble now?

It’s a legitimate question, but the wrong question.

Because if it could be answered, it would imply that acting on that answer is an effective strategy. It’s not.

The truth (one that has endured across every technological wave) is that it’s impossible to predict when Nvidia’s sales will slow or who the next Netflix will be. Long-term gains accrue not to investors who call the top or pick a winner, but to those who stay exposed to the broader currents of human ingenuity and capitalism. That means remaining invested when the market feels expensive and staying the course when it feels frightening.

A better question might be, what will this next transformation be like?

If the past is prologue, volatility will increase as the AI wave brings dislocations. Industries will be disrupted and jobs will disappear, giving way to new ones. Some of the early, big capital bets will prove wrong, rendering some firms profoundly overvalued. Many firms will stumble and never regain their stride; others will vanish entirely.

As markets contend with uncertainty, corrections could become more frequent. But if history is any indication, the foundation itself will be solid, and the friction is nothing more than the sound of the older economy giving way to the new.

Because no one can know how the AI transformation will unfold, investors can prepare for turbulence by taking a page from the corporate treasurer’s playbook and ensuring that a slice of their portfolio—especially capital needed in the short term—is allocated to the quieter, steadier returns of fixed income.

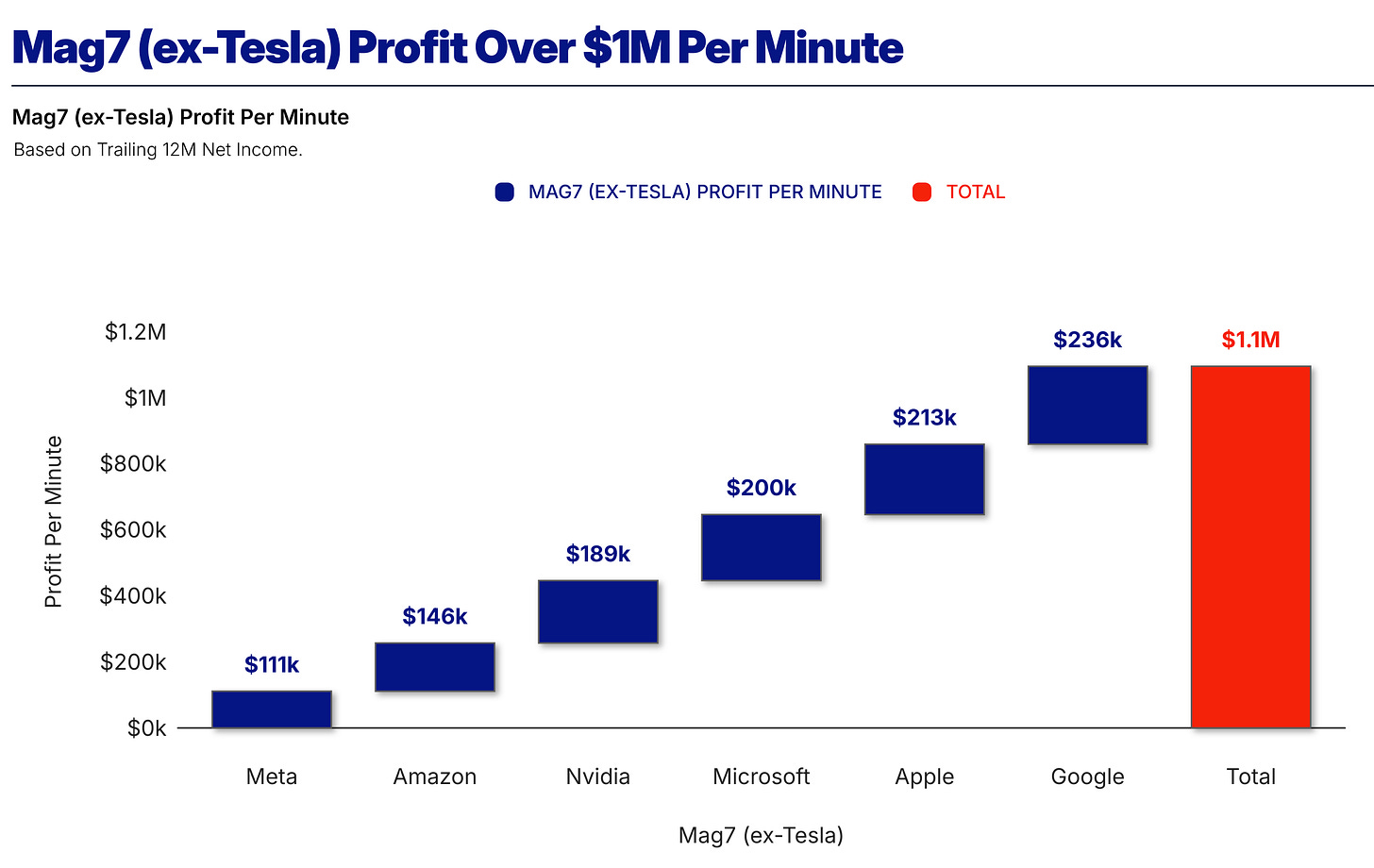

The good news for the growth portion of investor portfolios is that today isn’t 2000. Earnings aren’t promised; they’re present—at a scale the world has never seen. The modern family of tech giants (the Magnificent 7, as they’re often called) generates over $1 million of profit per minute.

One million a minute.

Over $500 billion a year.

Extraordinary.

Historic.

Broad and diversified equity ownership is essential for periods like this—because it ensures you hold today’s leaders while giving tomorrow’s winners room to enter your portfolio long before you know their names. After all, only one of the names in the chart above (Microsoft) was a giant in the 1990s, the others were the second- and third-order companies that emerged from the foundations laid in the dot-com era.

The same pattern is forming now; if history is any guide, there has rarely been a moment when the ground was more fertile. The infrastructure being built at unparalleled velocity is creating the conditions for new companies, new industries, and entirely new productivity to emerge.

The market may not be overvalued so much as undervaluing what’s to come. Investors are well served to remember that long-term compounding happens not by prediction, but by participation.

And all this movement of corporate capital gets me thinking about my own velocity—the times in my life when I’ve held my resources, attention, energy, and money in reserve.

Personal T-bills, if you will.

Looking back, it was prudent at times, necessary at others.

But then, life would serve up new opportunities, such as a different job, a second chance at marriage, starting a business, or becoming a father. And I’d be invited to activate those resources, to redeploy myself. To move from storing to building, from waiting to participating. Looking back, every leap was disruptive and frightening.

And yet...

I am reminded of a final truth: We are most alive in motion. Like capital, when in motion, we grow. We compound.

And over time, we transform.

Feedback Welcome. Leave a comment if you are inclined. I love hearing what resonates with you, and the comment forum is a beautiful source of learning. Reply to this message if you’d like to reach me directly.

Spread the Love. If you think someone would enjoy this essay, please share, or restack it. Readership spreads through word of mouth.

Leave a Like. If you enjoyed this essay, please click the ❤️ below.

James, if anyone doubts your deep understanding of the market and investing, I give you Exhibit A. I'm impressed with your knowledge, as well as your ability to unpack a very complicated subject, in an engaging manner, into something easily understood by those who aren't well-versed in this subject. Very well done!

My favorite line.

"A better question might be, what will this next transformation be like?”

The way you compare the current money situation to a hurricane economy, and how you reframe the hurricane economy is brilliant….and then to bring this all around to transformation to potential and possibility that we cannot even imagine, is so full of hope and expectation. I have been thinking about how the AI boom is exponential in comparison to the dotcom boom and wondering what is next with awe and wonder.

This doesn’t feel heavy to me, it feels like utter AWE!