The Risk is Us

Staying patient with our climbing partner

Returning to base camp, Edmund Hillary approached the crevasse he had crossed earlier. Four feet wide, it was too far to hop across. He spotted the giant chunk of ice jutting out from the other side, and like on the way up, it would make an easy stepping stone.

Before he could feel the safety of the ground under his second step, the ice chunk broke free.

There he stood—atop an ice mass.

Freefalling.

On the ice field above, Hillary’s partner, Tenzing Norgay Sherpa, slammed his ice axe into the snow, grabbed their connecting rope, and whipped the slack around the handle. Hillary slammed into the wall, and the ice chunk disappeared into the abyss, hurtling toward a splintering end.

Six weeks later, Norgay, a devout Buddhist, dug a shallow hole in the snow, pulled chocolates and biscuits from his pocket, and buried the sweets as an offering to the gods. Hillary pulled a crucifix from his pocket and buried it alongside as an homage to a different god.

On May 29th, 1953, connected not by their beliefs, but by a lifelong calling and the same rope, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay Sherpa stood where no one had stood before—on top of what Tibetans call Chomolungma – the mother goddess of the universe, what the Nepalese call Sagarmatha – the goddess of the sky, and what Sir George Everest recorded as the highest point on earth in 1852 at 8,848 meters (29,032 feet).

“At that great moment for which I had waited my whole life,” Norgay said, “my mountain did not seem to be a lifeless thing of rock and ice, but warm and friendly, and living,”

After refueling on mint cake and scouting a climbing route up a nearby peak, Hillary snapped a picture of Norgay. Then, the backup team on the 1953 British Expedition of Mount Everest began their descent, mindful of Hillary’s close call weeks earlier and aware that more lives are lost on the way down than on the way up.

“We thought since we’d climbed it, people would lose interest,” Hillary said years later.

Interest intensified. The climbing regimen evolved, and the Everest expedition industry was born. The following seven decades would see 6,600 climbers reach the top 12,000 times.1

What didn’t evolve? Human physiology and air. At 5,500 meters (17,500 feet), the air at Everest Base Camp contains about 50% less oxygen than at sea level. On top, oxygen levels drop to 33%. Dull-mindedness and dizziness are table stakes. Headaches and hallucinations are commonplace. Simple feels complex. Yes or no questions remain unanswered. Walking downhill feels like walking uphill.

If there is a marriage that starts compromised, man and sparsely oxygenated air are one. Acclimatization is required therapy. Climbers move up and down between camps in a carefully planned process—pushing higher and then retreating lower—day in and day out for eight weeks. They adapt gradually, connecting their unseeable insides with the hard-to-find oxygen on the outside.

Uncomfortable, often tortuous monotony for one twelve-hour shot at the top. Unless you are a sherpa. Native to the high mountain region of eastern Himalaya, it turns out sherpas have broader arteries and wider capillaries, enabling twice the blood flow of visiting climbers. Evolutionary genetics have earned sherpas a head start, needing only to acclimate to the mountain's upper reaches. Darwin would smile.

Most of us don’t dream of standing on top of the world—especially knowing what it would take to get there. But we do dream of retirement. We envision work flexibility or a more meaningful yet lower-paying vocation. We imagine time optionality. If retired, we dream of making it further down our bucket list.

Which is why we save. And why we invest.

As investors, we become climbing partners with the stock market. Like Hillary and Norgay, we rope ourselves together. But unlike Hillary and Norgay, our connection doesn’t last eight weeks; it lasts a lifetime. We discover the stock market is a fabulous and reliable long-term partner, taking us to heights never fathomed. We also discover the stock market is a vexing and unreliable short-term partner, taking us to lows that terrify us and test our resolve.

If we looked back to when Hillary and Norgay broke bread with the goddess of the sky, we would stand in awe of a climb even greater than theirs.

● In the two decades following their ascent, as the world endured the Korean and Vietnam Wars and John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King’s assassinations, the S&P 500 Index2 climbed from an index value of 25 to 85.

● During the 1970s and ’80s, as the U.S. contended with Watergate, Nixon’s resignation, and double-digit inflation, the stock market rose from 85 to 350.

● In the 1990s and 2000s, while digesting the dotcom bust, the 911 terrorist attacks, and the subprime lending crisis, the stock market ascended from 350 to 1,115.

● Over the last thirteen years, while crawling out of the financial crisis and battling a global pandemic, the stock market increased from 1,115 to over 5,000 today.

A 20,000% increase. A tripling or quadrupling every two decades.

A straight shot up? Riiiight.

A walk in the park? Hardly.

Like high-altitude climbers, the stock market constantly acclimatizes—pushing higher, then retreating lower. 53% up days, 47% down days. 80% up years, 20% down years. As investors, we are roped to our climbing partner and connected to the up-and-down acclimatization process. Unlike climbers, who determine when to retreat and for how long, we have no control over when, how fast, or how long our partner retreats. This lack of control stirs our insides. Agitates us.

Sharp falls frighten us.

On Monday, October 19th, 1987, investors felt like Hillary when the ice chunk broke free, as the market dropped 20% - in one day. The week after the 911 terrorist attacks, investors felt like they were backsliding down a glacier when the market fell 11% in one week. As the global pandemic enveloped the world in March 2020, it was as if a blizzard hit and fog set in over investors before plunging into a crevasse when the market lost 34% in one month.

In the seventy years after Hillary and Norgay stood 5½ miles above sea level while achieving stratospheric gains, the stock market acclimatized monumentally, pulling back at least 10% twenty-five times, falling more than 20% ten times, dropping 30% three times, plunging more than 40% two times, and crashing more than 50% once.

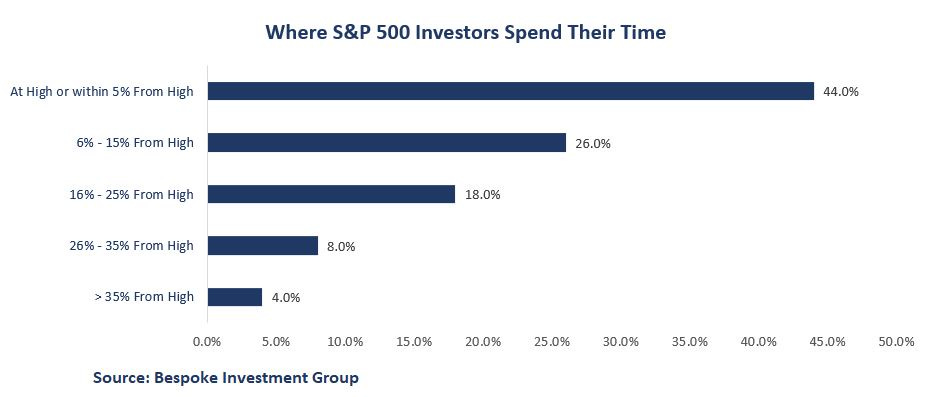

Yet, for all the stock market’s unplanned, inconvenient, and unnerving trips down the mountain, we must not lose sight of two things. First, 44% of the time, the market was within 5% of its high, and 70% of the time, it camped within 15% of its top. Despite our fears, most of the time, the market was acclimatizing near its top.

Second, every time the market slid down a glacier or fell into a crevasse, it arrested its fall, reversed course, and climbed upward to an even higher high than before. Unlike Mt. Everest climbers, who will never stand above 8,848 meters, our climbing partner has yet to reach a permanent top.

All investor problems stem from our inability to sit quietly with our emotions while staying roped to our climbing partner. Altitude sickness lurks in headlines we don’t like, current events we don’t understand, and outcomes that don’t come to pass. Emotional sickness takes hold when our partner suddenly turns downward.

Like climbers, we must acclimatize. Our marriage with the market—our staying roped in—depends on it.

We acclimatize by countering our fears with perspective. When markets are high, we become fearful. Doubts creep in. We get scared the market is due for a retreat. We become attached to our gains. How dare we give them back? We tell ourselves, “I’ll just unhook my rope and hang out here while my climbing partner heads down the mountain.” We delude ourselves by believing we’ll rope back in when the coast looks clear.

With perspective, we remind ourselves that not only do markets spend most of their time near highs, but current highs beget more highs. When we fear our climbing partner is due for a big fall, the opposite usually occurs. One-year investment returns from all-time highs exceed one-year returns from all other starting points. And about one-third of the time, when the market notches a new all-time high, it continues upward and does not drop back below the high it just made. Over time, today’s peaks become tomorrow’s base camps.

When markets are falling, we acclimatize by summoning patience. When losing money, our fears turn to anxiety—dread. We want our discomfort to stop. We tell ourselves we knew better and should have acted when the market was high. Then we bargain: “I’ll unhook my rope—let my partner keep going down and reconnect once the dust has settled and the market is rising again.”

What if we knew that historically, those 10% trips down the mountain take about three months to bottom and about three months to recover? The 20% slides—about seven months to bottom and eight months to recover. And about that 30% pandemic plunge—a one-month drop and a four-month recovery.

When our partner is done descending, its upward turn is often rapid and forceful. After the pandemic bottom, the market notched one-day gains of 9%, 7%, and 6% over 2½ weeks. The risk isn’t that we keep falling. The risk is that we get left behind when our partner resumes the climb.

In 1914, Namgyal Wangdi was born to a Tibetan yak herder and his wife. As a child, Namgyal attended a local monastery and was given a new name: Tenzing Norgay. Chosen by the head llama, Tenzing means “thought grasper” or “thought holder,” and Norgay means “increasing wealth.”

As investors, may we grasp that the risk to our retirement, to a more meaningful vocation, to time-optionality, and a greater number of bucket list experiences lies not with our climbing partner but with ourselves.

May we acclimatize by broadening the arteries that attend to our perspective and widening the capillaries that serve our patience.

May the result be increasing our wealth3 and, more importantly, our well-being.

3 The word "wealth" comes from the Old English word Weal - meaning "a sound, healthy or prosperous state. Well-Being."

2 The Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P500). A diversified index of the largest 500 US stocks, weighted by market capitalization. "The market," "market," and "climbing partner" refer to the S&P 500.

1 Sherpas are responsible for the majority of the repeats. Kami Rita Sherpa holds the record for the most ascents of Mount Everest. He recorded his 28th summit on May 23, 2023.

Thank you for reading, and I’m sorry for the length. I hope you made it through and it was worth it.

Leave a Like. If you enjoyed this essay, please click the ❤️ below.

Spread the Love. If you think someone would enjoy or benefit from this essay, please share it.

Reach Out. If you’d like to connect, reply to this email, leave a comment, or DM me through Substack.

I love how this turned out James. Such a satisfying blend of storytelling and hard data, this is a piece I’ll return to again and again as I navigate my financial journey.

And so good to see you publishing and putting your ideas out there. The world is a better place because of it (:

Such a treat to have a James Bailey piece in my inbox.

My husband is a long-term investor, holding companies for years. I imagine you two might have a similar approach to this whole investing thing. Thanks for breaking it down for us in such a visual way.