This Time Is Different

What you should do remains the same

“We don’t see things as they are. We see things as we are.” – Anaïs Nin

Wednesday, November 5th, 2008. The sun wasn’t up, and the stock market hadn’t opened. My phone buzzed incessantly—six calls in 90 minutes. The night before, Barack Obama was elected president, to go along with a blue House and Senate. A half-dozen distressed clients were on the other end of the line. Bewildered. Anxious and scared. Each convinced the country was headed in the wrong direction and the market would crater. They wanted out.

By the afternoon, calls came in from delighted clients. Elated. Optimistic and hopeful. Each described a rosy future—several even saying they were sitting on some capital to invest. They wanted in.

Wednesday, November 3rd, 2010. The Tea Party wave washed ashore the night before, and Republicans retook the House. Before daylight, the same dynamic started to play out, only this time, the distressed and delighted clients traded places. “The march to socialism has been arrested,” said one. “Gridlock will kill the recovery,” claimed another.

Wednesday, November 9th, 2016. For a brief moment, inconceivable today, clients formed a chorus—united in uncertainty—and most wanted out. On the eve of the election, economist Paul Krugman predicted in The New York Times that if Donald Trump were to win, the stock market could fall “by epic proportions.”

Few remember Krugman’s prediction today; fewer remember what ensued. From November 2016 through January 2018, the S&P 500 notched fifteen consecutive months of positive returns—eclipsing an eleven-month streak that had stood since Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency.

Today. Here we are on the eve of Trump’s second inauguration. Once again, half the country is unsatisfied, anxious, and scared, while the other half is satisfied, happy, and hopeful. Once again, investors uncomfortable with the current political landscape are contemplating changes to their portfolios, believing that this president, his cabinet, and a red-colored Congress represent a grave danger to their hard-earned capital.

Once again, investors are well-served to keep a healthy distance between politics and their portfolios.

Why?

Because parties and policies aren’t the main drivers of portfolio performance. Markets move consistently higher, regardless of who is president or who controls Congress.

A different view isolates each presidential term and baselines the starting point. While spectacular returns during the eight-year terms of Reagan, Clinton, and Obama stand out, the predominantly positive returns across administrations tell the real story.

(Note: Biden's return line would look much like Trump's, but the chart date range had not been updated to include 2024.)

Consider the twenty-four years from 1976 to 2000—spanning Carter, Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Two Republicans. Two Democrats. Different beliefs, priorities, and policies. Despite their differences, the outcome for investors was the same: growth. At the start of Carter's term, a $1,000 investment in the S&P 500 grew to $29,000 by the end of Clinton’s presidency, an annualized return of 15%.*

If markets rose solely due to policies specific to a party, we’d see clear blue or red winners. We’d experience whipsawed returns. Instead, markets rise because the collaboration of humans to create goods and services for customers—and profits for owners—triumphs over politics. While politics matter in society, earnings from innovation, ingenuity, and business creation matter far more in the context of your portfolio.

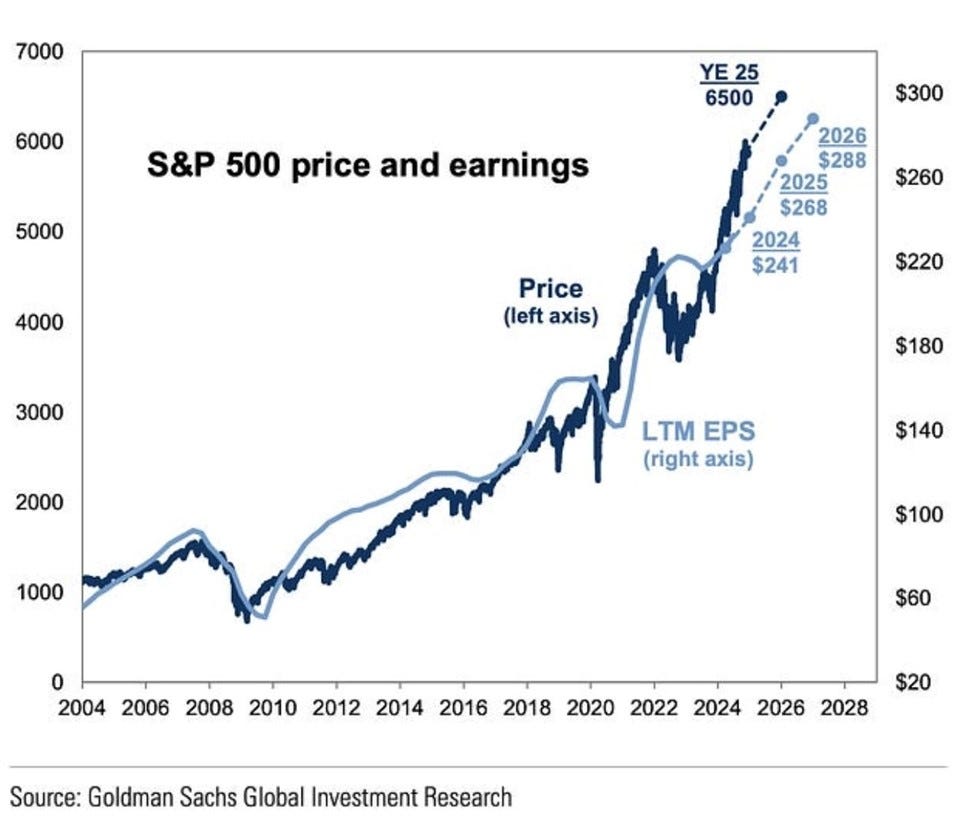

Consider another, more recent, twenty-year stretch depicted in a chart overlaying earnings and market price. At the beginning of 2004, S&P 500 earnings hovered around $50/share, while the index traded near 1,100. After companies close their books for 2024, earnings are expected to reach $240/share, while the S&P 500 trades near 6,000.

During this period—again marked by two Republicans and two Democrats, a global financial crisis, a pandemic, and resurgent inflation—a $1,000 investment grew to over $7,700, delivering a 10.3% annualized return.* While less than 15% annualized from 1976-2000, investors would gladly take it.

What stands out most in the chart is how companies grow earnings through time—not linearly, not without temporary plateaus and periodic pullbacks—and how connected the market is to earnings.

Worried about where the market is headed? Look to earnings, not elections.

“The four most dangerous words in investing are: ‘this time it’s different.’”

– Sir John Templeton

While our inboxes haven’t blown up as they did after Trump’s 2016 victory, we’ve received a steady drumbeat of concerns after his reelection. Client conversations often begin with “It feels different this time,” followed by unease about tariffs, trade wars, tax rates, and deficits. The same questions arise repeatedly: “Who will the winners and losers be? What actions should we take now?”

Our response? It is different this time, as it was for George Bush, who inherited a dot-com bust and presided over a terrorist attack. As it was for Barack Obama, who inherited a global financial crisis. As it was for Joe Biden, who contended with a worldwide pandemic.,

Even though it feels different this time, the optimal response remains the same for investors: Sit still and avoid unnecessary action.

Why?

Consider the CEOs of the most significant holdings in your portfolio: Tim Cook at Apple, Satya Nadella at Microsoft, Andy Jassy at Amazon, Jensen Huang at Nvidia, and Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway. These leaders and thousands of other CEOs in your portfolio are already navigating the myriad variables affecting their businesses—tariffs, tax rates, and more. Together with their teams, they are already acting and making the best decisions to drive company earnings—your earnings as an owner.

Additional actions, layered on top of theirs, will likely diminish returns.

Why?

Because it’s what the data reveal.

We need to look no further than the track record of active fund managers—managers who claim their proprietary research will translate into stock-picking and market-timing actions that will yield investors superior results over time.

Since 2002, S&P Dow Jones Indices have tracked the performance of active fund managers versus benchmarks. The left side of the table above shows that in any given year, the odds are about a coin-flip that the managers who "act for a living" lift return against their respective benchmarks.

The right side of the table shows that fewer than 10% of these active managers have outperformed the broad S&P 1500 index over extended (10+ year) periods. Further, according to S&P Dow Jones, those who outperform in a given period fail to repeat their success in subsequent periods, reinforcing the importance of discipline—true discipline being the ability to sit still.

If investing came with a warning label, it might read: Unnecessary action can be harmful to returns.

“The big money is not in the buying and the selling, but in the waiting.”

– Charlie Munger

Tuesday, November 4th, 2008. By the night of Obama’s victory speech in Chicago’s Grant Park, the S&P 500 had fallen 35% from its all-time high in October 2007. It continued its freefall over the next four months, dropping another 33%. Was any of this Obama’s doing? Or was it simply the market not yet finding its bottom amid the financial crisis?

Conversely, was the market’s performance following Trump’s 2016 victory his doing? Or were the gains simply a result of company earnings accelerating in his first year?

These unanswerable questions are a reminder that, in the short term, the market has a mind of its own.

Corrections are perhaps even more unnerving than elections—even the perception that one might be lurking around the corner. As Trump begins his second term, the S&P 500 has advanced almost 60% over the past two years. Some might say the market has run too far, too fast.

Who is to say?

While we can never be sure of the catalyst or pinpoint the reason, corrections occur regularly and are a part of a well-functioning market. And even though our emotions wish it were so, corrections cannot be reliably predicted. They can, however, be planned for with a portfolio's allocation to fixed income.

When the next correction finally shows up, the charge is the same as with elections: resist the urge to act. Instead, sit still, and in the words of the late Charlie Munger, “wait” for the return.

It has never failed to come, and when it arrives, you won’t want to miss out.

I love the title of your publication, and more so, I love when your posts blend money and meaning.

Having recently started to get to know you better, I know everything in your world has meaning, and money cannot be divorced from meaning.

Here’s the deeper meaning I see in this article.

The greatest (and perhaps only fear) of humans is the fear of the unknown. When your clients call you and ask you to be a crystal ball gazing prophet about what’s going to happen as a result of the latest election or inauguration, they are expressing their deepest fear, the unknown.

Your answer is threaded through every paragraph of this post with simple stability. Have faith. Stay steady. Stand solid. Everything always changes, and in those changes, we grow, and in that growth we learn to adapt, and in that adapting, we grow. The human condition is to face the unknown, stay steady in the faith and trust in humanity that no matter what happens, dot.com bust or real estate market crash or global pandemic, we always learn to adapt and GROW.

It just strikes me that this goes way beyond finance and investing. I know that's obvious to you, but it's a huge lightbulb for me. I just never connected these dots. I think I'm going to need to hear you say it many times over in different ways for it to sink in. I know that shouldn't be the case, but I'm saying it out loud because I'd bet I'm not the only one who reads something like this and feels as though I am being asked to walk on the moon. You don't know what you know when you're an expert, and this very basic message is so important, but it's the person you are who can hold on and stay stably seated that is the real gift. I need to be around that grounded faithful energy in relationship to finance. Your stories please.